ONCHI

COLLECTING JAPANESE PRINTS FEATURED SOSAKU HANGA ARTISTKoshiro Onchi

1891 - 1955

The sosaku hanga movement would not have flourished as it did without the spiritual wisdom, guidance, and inspired leadership of Onchi Koshiro. A founding member of numerous organizations that served to educate and inspire subsequent generations of sosaku hanga artists, Onchi was also a noted publisher of literary magazines, abstract art, and poetry.

The fourth son of Onchi Tetsuo, he was born in Tokyo in 1891. After graduating in 1909 from the Middle School for German studies, Onchi studied oil painting at the Aoibashi branch of the Hakubakai institute and began sending impressions of the recently published book Yumeji Picture Collection, Spring Volume to the artist Takehisa Yumeji, for whom Onchi expressed great admiration. At the behest of Yumeji, Onchi enrolled at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts the following year, where he studied oil painting and sculpture; however, Onchi was also a rebel at heart, and in 1911 withdrew from the school. Through his newly-established friendship with Yumeji, he obtained a job as a book designer with Kawamoto Kamenosuke of the Rakuyodo publishing house, before being readmitted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts a year later. In October of 1913, alongside fellow students Tanaka Kyokichi and Fujimori Shizuo, Onchi began publishing the epoch-making print journal Tsukuhae which ran until 1915. Notably, Onchi's series Lyric was considered the first purely abstract imagery produced in Japan. A year later, he joined poets Muroo Saisei and Hagiwara Sakutaro in producing the magazine Kanjo; as he did with Tsukuhae, Onchi contributed multiple cover designs, poems, and mokuhanga.

In 1917, Onchi published his first solo collection of prints, Happiness. In 1919, he participated in the Nihon Sosaku Hanga Kyokai's inaugural exhibition (later becoming an active member) and remained committed to it through its reorganizing as the Nihon Hanga Kyokai. In 1921 he began publishing the art magazine Naizai with Otsuki Kenji and Fujimori Shizuo. Over the next several years, Onchi continued to publish a variety of poetry and print magazines in which he championed the idea that printmaking was a legitimate and expressive medium and not merely a means of reproduction. He contributed to a number of journals, including Minato, Kaze, Shi to hanga, Dessan, HANGA, Shiro to Kuro, Han Geijutsu, Kitsutsuki, and numerous other collective series.

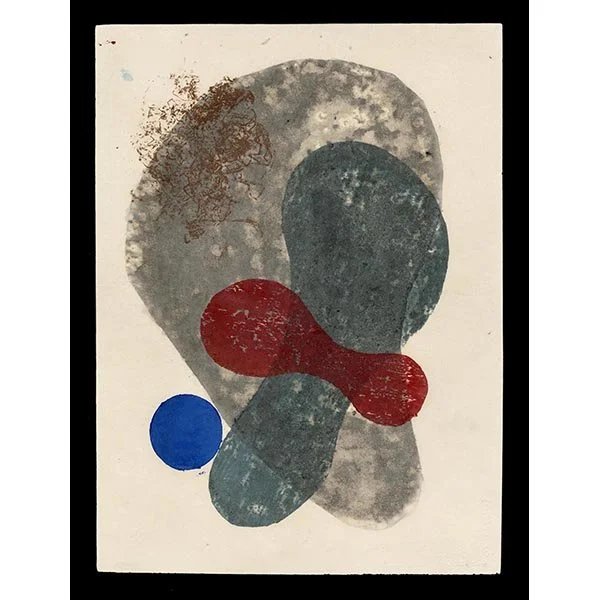

By 1927, Onchi had firmly established his reputation as a book designer and contributing author. He also made many figurative works in woodcut and multiblock techniques using natural materials such as strings, leaves, and charcoal, as seen in Umi no Dowa (1934), Hiko kan no (1934), and Mushi, Uo, Kai (1941). From 1935 through the next nine years, Onchi edited one hundred and three issues of the monthly magazine Shoso, later becoming a criterion of excellence in graphic design. He also personally designed more than one thousand books and published several books of his own illustrated poetry, including Fairy Tale of the Sea (1932) and A Diary of Random Thoughts (1935).

In 1949, Onchi received the very first prize offered in Japan for book design, deservedly so. In the midst of his busy career, he contributed to One Hundred Views of New Japan in 1938 and, from 1939, throughout the postwar period, maintained the Ichimokukai organization. Onchi was further active in progressive organizations after the war, including the Japan Abstract Art Club and International Print Association. During the Occupational period, Onchi's works caught the eye of William C. Hartnett of the Army Education Center as well as Oliver Statler, an American financial officer. Soon after that, Statler promoted Onchi through his book, Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn (1956), and the sosaku hanga movement as a whole. As a result, Onchi's work was rapidly acquired by major American and British museums, private collectors, and many peripheral sosaku hanga artists rose to prominence.